Unaccompanied immigrant minors face major immigration court hurdles.

In U.S. President Donald Trump’s immigration policy, the fate of unaccompanied minors hangs in the balance. The administration has not made clear what it will do with these young immigrants. Much depends on the ongoing negotiations in the House of Representatives regarding the DREAMers. Trump has already stated that any deal for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients will include provisions for the unaccompanied minors.

According to the Council of Foreign Relations, the first provision, which focused on border security, instructed federal agencies to construct a physical wall “to obtain complete operational control” of the U.S. border with Mexico. The second, zeroed in on interior enforcement, broadened definitions of those unauthorized immigrants prioritized for removal, ordered increases in enforcement personnel and removal facilities, and moved to restrict federal funds from so-called sanctuary jurisdictions, which in some cases limit their cooperation with federal immigration officials. This rule also expands the application of “expedited removal” to anyone who cannot prove they have been in the United States for two years, allowing them to be removed without a court hearing.

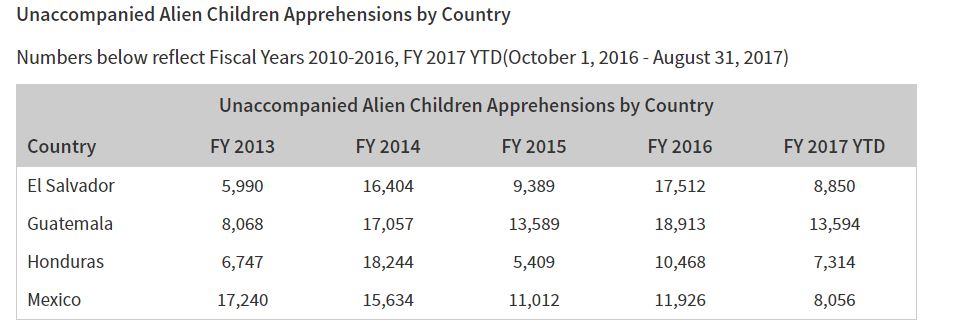

Due to conflict, strife and gang violence in places like Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, parents decide to send their young children through a crossing from Central America to Mexico and then the U.S., hoping their children will find a better and safer life. The treacherous journey these young people undertake is riddled with insecurity and dangerous rail crossings on trains such as “La Bestia” across into Mexico.

Once these minors cross into the U.S., there is an uncertain and frightening future.

Voice Latina interviewed two lawyers – one an immigration attorney and the other practicing family law. Both essentially said that the fate of these minors is caught up in myriad of complications facing the U.S. in their immigration policy.

Lymari Casta, the immigration attorney, noted that sometimes she as a lawyer does not always know where her client is. There are instances when she arrived at a detention center and her client has already been moved to another jail sometimes out of state. There is often a haphazard way that the immigration court moves. This has to do with the number of cases judges and magistrates are assigned, sometimes hundreds or it can range to thousands. Beginning with the glut of cases and the lack of judges and magistrates nationwide to the slow movement of the immigration docket, it can be a year to two or three years until a case is heard.

The welfare and safety of the minors are important. The youngsters are placed with relatives that can look after them or in other instances, when no one can be found, in the care of a federal agency. The cases of these minors many times linger yet they almost always have access to a legal defense.

So far, none of the immigration policy arguments addresses the practical and everyday stumbling blocks that the U.S. immigration systems face. The stagnation in Immigration Court means arduous hurdles and long waits that undocumented immigrants endure, the myriad of rulings, that take them from one detention center to another and immigration attorneys having to keep up with all of this as they await the outcome of their cases.

This past summer was a particularly busy month in the immigration debate in the U.S., not only for unaccompanied minors but also for DACA recipients who faced in the fall the decision from the Trump administration that they would rescind former President Barack Obama’s executive order allowing DACA recipients to stay in the country legally with the ability to work. The work of where the U.S. immigration policy will go stands with House of Representatives Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wisc. In the past, he has indicated that he would work toward normalizing the status of millions of undocumented immigrants – that was before President Trump’s fierce opposition to legalization. As it stands now, it will not be until next year that perhaps meaningful legislation will make it to the floor of the House to be debated and sent to the President.

Verónica Escobar (VE): Immigrants come in every stripe, they come from different countries not only Latin America, but from all over the world. Some people are fleeing persecution, violence, poverty, and some people are just looking for a better life.

Lymari Casta (LC): Unaccompanied minors are children that cross the border and usually not accompanied by an adult, such as a parent. They come usually escaping very dire circumstances usually in Central America – Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. They are apprehended and put into detention centers catered to children. Usually these children came here to meet with relatives that they have here. Now a lot of these relatives, or maybe most of these relatives are also undocumented.

The relatives usually can go and pick up the children if they pass certain requirements. They don’t necessarily have to be here documented, in immigration terms, so their parent or uncle, who meets certain requirements, can pick up the child.

VE: In order for the immigration court to entertain the child’s application for a green card or for legal residency, you have to have been found by a family court to be a child in need of protection and that’s what special immigrant juvenile status (SIJS) is. They deem you a neglected or abused child, that you don’t have family in your native country and that if you went back, you would be in danger and that you would be subjected to more neglect and abuse.

If the child can show that they don’t have family in their country of origin, or that they’re going to be subjected to abuse or maltreatment, if they go back home, and if they seem well settled in this country and they have a better life, more often than not the special immigrant juvenile status application is successful. And what I’ve told clients of mine, that I’ve assisted doing those proceedings, is that this is only the first hurdle. The most difficult hurdle is the immigration court. It’s one thing to have the SIJS finding, it’s another to be granted your green card and to have legalized status.

LC: There has been even before this administration quite a backlog in immigration cases being heard before immigration court and judges. Now, this problem has been aggravated because of the efforts of apprehending and detaining people, so, a very already saturated immigration court system has been more bombarded by more cases.

VE: Courts in general, you have judges and you have cases. Sometimes you don’t have enough judges for the cases that come in, so cases are going to lag behind because judges have very high calendars. And there are only so many hours in the day, so many days in the week, so many days in the month for cases to be processed. If a judge has thousands of cases but there’s only one judge and there’s only so many hours in the day, the week, and the month, your cases are going to lag behind and they are going to take time to be processed.

LC: For example, if you need to present a case for asylum, because of the saturation of the courts and the calendars are so full, my clients case may not even be heard for one, two, three, even four years.

VE: But the problem is there aren’t enough immigration judges nationally to go around to handle, not only the cases that are still pending, but the increase in filings. There are magistrates that handle these cases and there are judges. Again, there are no real easy fix to it because like I said before the immigration system has been broken for decades, and it has always taken a long time for immigration cases to process.

LC: It’s very important for people to understand they have rights. They have a right to an attorney, they have a right to remain silent, and they have a right to not sign anything against that would put their case in danger and they are going to be expeditedly removed.

Sometimes when people are apprehended, they are very fast flown to another state and it takes a long time before we know where these people are. It happens all the time. I do cases all over the U.S. and sometimes I’m on my way over to visit somebody at a jail and when I get there, they have already been moved to another jail, to another state. I’m an attorney and I have access and I know how to find people. Imagine the person who doesn’t have legal representation and their families have no idea how to find their relative or their friend. It’s a very sad and stressful situation.

VE: The issue of undocumented immigration into the U.S. is decades old. As long as my parents have been here, there has always been undocumented immigration. The immigration system is broken and that has led to what we look at today.

Courtesy of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, CBP.